|

|

|

|

|

|

History |

|||||

|

|||||

RHODESIA - MZILIKAZE TO SMITH (Africa Institute Bulletin, vol. 15, 1977) The Rhodesian problem is essentially the outcome of white and black settlement in Southern

Africa, and the resultant confrontation between two societies - West European and African, and the central issue today revolves round the continued survival of whites, and the contribution they can, or will be

allowed to make to Rhodesia's future development. Modern Rhodesian history dates back to the Matabele migration from the Transvaal in the late 1830's when they arrived in the area now known as

Bulawayo. The Matabele, a scion of the Zulu nation, under their Chief Mzilikaze, were driven from the Transvaal after attacks on the Voortrekkers. Their encroachment on the land north of the Limpopo marks that

first repercussion white settlement in Southern Africa was to have on the course of Rhodesian history. The Matabele were a predatory race, and established themselves in their new environment by

subjugating the original inhabitants until they were firmly entrenched as rulers of the territory between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers. Their impis foraged far and wide across the land, looting cattle and

capturing women and children. Before the coming of the Matabele, the Bushmen, who left their paintings in remote caves, and the negrohamitic peoples, who had migrated from the lakes of Central Africa were the

occupants of Rhodesia. This migration brought the Mashona to Rhodesia, possibly sometime in the 1500's. There were also the builders of Zimbabwe, and numerous other imposing stone structures, who left no other

record of their passing save silent ruins scattered about the land. By the last half of the 19th century, when whites started taking an interest in the land north of the Limpopo, the Matabele and the Mashona were

already firmly established in the area.

THE SCRAMBLE FOR AFRICA

The first whites to reach Rhodesia were missionaries, hunters and trekkers who crossed the Limpopo in search of grazing. Missionary-explorer David Livingstone was the first white man to reach the

Victoria Falls, doing so in 1855. Four years later Robert Moffat established Inyati Mission, the first permanent white settlement. In subsequent years whites arrived in ever-increasing numbers, but were with few

exceptions temporary visitors and not settlers or colonists in the accepted sense. The first actual white settlers in 1890 took part in what is termed the scramble for Africa, preceded and triggered

off by the discovery of diamonds and gold in South Africa. During the 1880's European imperial powers like Germany, Portugal and Britain showed a growing interest in land north of the Limpopo. The

Portuguese already had colonies on the East and West Coasts of Southern and Central Africa, and British penetration from the south was to prevent them from linking their territories across Africa. Germany found

herself in much the same position as Portugal and her interest in the Transvaal Republic was growing steadily. Transvaal too had put out tentative feelers towards the north, which could ultimately have led to the

linking of German and Transvaal territory, thereby severing the path of British advancement. Such was the position in the 1880's when Cecil John Rhodes, politician and mining magnate, who gave his

name to Rhodesia decided to act. John Smith Moffat, at the instigation of Rhodes per- suaded Lobenguela, who had succeeded Mzilikaze in 1868, to sign the Moffat Treaty in 1888. In terms of the treaty the Matabele

agreed not to enter into correspondence or treaty with any foreign power without the sanction of the British High Commissioner for South Africa. The Transvaal and Portuguese Governments both objected

to the Moffat Treaty, but the British Government remained adamant. Later during the same year British advancement into Central Africa was finally secured when Lobenguela signed the Rudd Concession

giving Rhodes 'complete and exclusive charge over all metal and mineral rights' in Rhodesia in return for a monthly payment of £100 to himself and his heirs. In addition to this, Lobenguela received 1 000 rifles

and 100 000 rounds of ammunition.

THE BRITISH SOUTH AFRICA COMPANY Besides mineral rights, the Rudd Concession also conferred sweeping commercial and legal powers on Rhodes. Armed with the Concession, Rhodes used his considerable financial

resources, derived from control of De Beers and Gold Fields of South Africa, to form the British South Africa Company (BSAC) that subsequently obtained a charter from Queen Victoria in 1899. The charter granted

the BSAC the right to operate in all Southern Africa, north of Bechuanaland (Botswana), north and west of the Zuid-Afrikaanse Republiek (Transvaal), and west of the Portuguese possessions. No northern limit was

stipulated. The first pioneer column, 180 men and 500 troops in employ of the BSAC left Kimberley for Rhodesia in May 1890, and established Fort Victoria in August 1890. A party of pioneers,

including the famous hunter, Courtney Selous, continued further northwards, and in September 1890 raised the British flag at what is now Salisbury. The pioneers dispatched a party to Eastern Rhodesia

to obtain a concession from Chief Mtasa thereby securing the country's eastern border with Mozambique. Border disputes however persisted, finally leading to an armed confrontation between the BSA Police and the

Portuguese in 1891. The Portuguese were defeated, and the boundary dispute was settled at the Anglo-Portuguese Convention in June 1891. The BSAC then turned its attention to the consolidation of

Rhodesia. A railroad had to be constructed from Kimberley to Bulawayo, growing unrest and strife among the Africans quelled if law and order were to be maintained, and the country was to attract colonists and

capital. In 1892 Dr Leander Starr Jameson, close associate of Rhodes, was appointed Chief Magistrate for Mashonaland. Jameson believed the Matabele could be absorbed peacefully into the country's

labour force, and attempted to secure a modus vivendi with them, based on segregation by designating a boundary between them and the Mashona. He also tried to prevent the Matabele from entering Mashonaland, except

as labourers. The latter were however not to be deprived of their traditional raiding grounds. After numerous incidents, matters finally came to a head in 1893 when a Matabele impi raided the Fort Victoria area to

punish local blacks for cattle theft. After a skirmish between whites and a Matabele impi, Jameson finally decided that the Matabele had to be put down, and plumped for war on 18 June, 1893. Although

the Matabele enjoyed a vast numerical superiority, the whites defeated them with their sophisticated weapons (The Maxim gun among others), and greater mobility. The Matabele then fled northwards.

During their pursuit of the Matabele, Major Allan Wilson and 31 men were trapped and killed to a man on the banks of the flooding Shangani River following a fierce engagement that put an end to the uprising.

Lobengula died somewhere in the Wankie area during the flight of the Matabele, and an era of peace and prosperity followed. Bulawayo boomed during the next years. The peace did not last long however.

A rinder- pest epidemic spread through the country in 1896, decimating cattle herds. White veterinary officers aggravated matters by shooting cattle belonging to blacks in an effort to prevent the disease

spreading. Other causes of discontent among the blacks were BSAC's land and labour policies and a taxation system. When Jameson was defeated and captured during his abortive raid into the Transvaal in December

1895, the blacks decided to put an end to white settlement in Rhodesia. In the absence of the troops who had accompanied Jameson, the second uprising proved far more serious than 1893 rebellion, and the BSAC was

forced to summon aid and reinforcements from the Cape. Sir Fredrick Carrington set out with a total force of 2 000 whites and 600 black soldiers, and finally drove the remaining impis into the Matopos where they

were blockaded. Rhodes arrived in Rhodesia from London at this time, and decided to take a hand in matters. In October 1896 he went into the Matopos to meet the Matabele chiefs personally, persuading

them to relinquish their arms and to surrender. By that time however the trouble had spread to Mashonaland. The Mashona rebellion was finally put down by the BSA Police assisted by a force of Mounted

Infantry under Command of Col Edwin Alderson (who was to become Inspector-General of the Canadian Forces in World War 1). Conditions in Rhodesia improved considerably in the period immediately after the Boer War

(1899-1903). Although the discovery of a major gold field still eluded the BSAC, numerous small mines were being opened up, and steady stream of immigrants, keen to escape from the depression following in the wake

of the Boer War, were arriving from South Africa. While the BSAC did not do much to encourage agriculture at first, land was plentiful and handed out freely. After much trial and error, farming

became established and within 20 years of the first pioneers entering Rhodesia the ground roots of a sound agricultural industry had been established. Rhodesia was offered her first opportunity to

join the Union of South Africa in 1910, and Charles Coghlan, who later became the first Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia, attended the National Convention in Durban in 1908 as unofficial representative from

Rhodesia. Ironically enough, Coghlan, who was to lead the anti-Unionist movement in Rhodesia during the 1922 referendum, felt in 1908 that Rhodesia should join the Union, but that the time for such a move had not

yet arrived. After 1910 anti-BSAC sentiment mounted in Southern Rhodesia, and an increasing number of settlers felt that the country should be placed under British rule. Britain however did not see

her way clear to taking over the burden from the BSAC at this time. The BSAC attempted to fuse the two Rhodesias - Northern and Southern - during the years immediately after the World War I, however,

Southern Rhodesia was wary of the large black population she would acquire by this move, and the scheme was finally rejected in 1917.

BRITAIN STEPS IN During the following year the Privy Council handed down a long-awaited decision. The case had

been put before it in 1914, and concerned the land question in Southern Rhodesia. Elected members of the Legislature contended that the BSAC did not own unalienated land in its private capacity, and that revenue

from unalienated land should be used for the administration of the territory instead of being appropriated by the BSAC. Following the Privy Council's decision in favour of the Legislature the BSAC

lost the economic motivation to govern the territory, and claimed £7 688 000 from the British Government for reimbursement of administrative deficits. It then seemed that a South African solution was the best

answer to the Rhodesian dilemma. A referendum was held in 1922 to determine whether the territory should become the fifth province of South Africa, and the anti-Unionist movement carried the vote by a majority of

2 785. The British Government formally annexed Southern and Northern Rhodesia in 1923, and paid the BSAC compensation amounting to £3 750 000. Southern Rhodesia in turn was to reimburse Britain to

the extent of £2 000 000. The first general election was held in 1924 and Coghlan became the first Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia after the territory had been granted self-government. The British Government

did however retain the right of assent in matters pertaining to black rights. Godfrey Huggins (later Lord Malvern) became Prime Minister in 1933, a post he held until Southern Rhodesia became part of

the ill-fated Central African Federation in 1953.

LAND TENURE AND FRANCHISE A brief look at the franchise and the system of land tenure during the period 1923-1953 is warranted. With the granting of self-government in 1923 Rhodesia retained the Cape

Colony system which gave voting rights to blacks and whites who owned property to the value of £150 or had an annual income of £100. Both means tests were accompanied by a simple language test in English. These

voring qualifications for a common voters' roll were maintained until 1951, when the financial qualifications were raised. Blacks had the right under the 1898 Constitution to acquire and dispose of land in

the same way as whites, but few of them ever exercised this right. The Morris Carter Commission was convened to look into the matter in 1925. Its recommendations were embodied in the Land Aportionment Act of 1930

(amended 1941), which allocated the land (50 percent to whites, 33 percent to blacks and rest remaining unallocated). While the Land Apportionment Act did guarantee the land rights of blacks, thereby

protecting them from exploitation, it engendered much bitterness, and remains a most contentious issue in Rhodesia. Recent legislation by Prime Minister Smith amending the Land Tenure Act to give blacks access to

agricultural industrial and commercial land resulted in the most critical test of his leadership since UDI when 12 members of the RF party opposed him in Parliament. (The Land Apportionment Act was redrafted, in

1969 and renamed the Land Tenure Act. In terms of the new Act blacks and whites were allocated an equal area of 45 million acres (18210 000 ha) each, while the remaining land, about 10 million (4047000 ha) acres

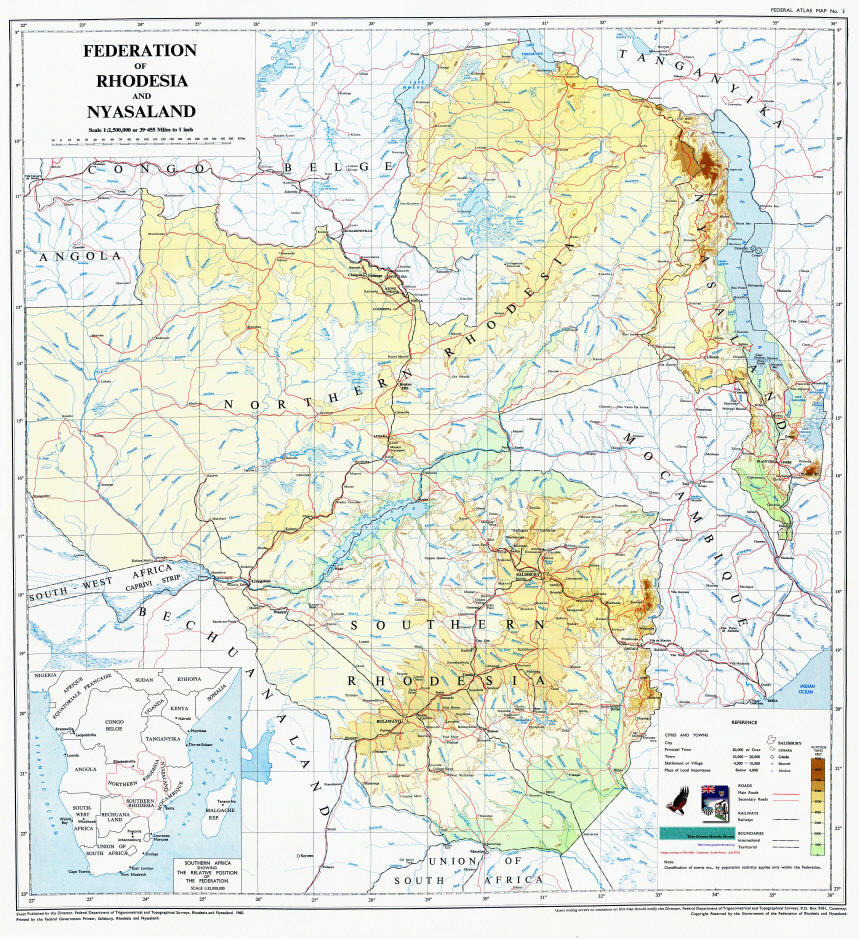

was designated national land for use as parks, nature reserves etc.) FEDERATION OF RHODESIA AND NYASALAND The idea of Federation, increasingly bandied about in

the late l940's, was not new and had been mooted from time to time. Events after World War II - the economic boom in Central Africa, and the rise of the South African Nationalist Party from 1948, regarded as a

threat to British interests in Southern Africa - all helped to crystalise matters. Despite the misgivings of certain black leaders, Huggins and Roy Welensky, from Northern Rhodesia, ardently supported the

Federation concept, and relentlessly pressed the British Government to go ahead. The Federation was finally constituted, following five conferences held between 1951 and 1953 as well as a referendum in the

territories concerned (Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland). The conferences were initiated by the Labour Government (that had agreed to Federation in principle, but held certain reservations about

black rights), and completed by the Conservatives that came to power in November 1951. The first Federal election, held in 1953, was based on universal suffrage, and the same voting qualifications

applied to all races. The voters returned the United Rhodesia Party (later the United Federal Party) with 24 seats out of 36. Despite overwhelming support for the Federation in the 1953 referendum, and the

sweeping victory of the UFP, black nationalists were extremely hostile towards the Federation, and their discontent finally led to a period of traumatic violence and lawlessness. When Huggins became

Federal Prime Minister in 1954, he was succeeded in Southern Rhodesia by Garfield Todd, the New Zealand-born missionary. Todd was soon at loggerheads with Federal thinking. He refused to extend power and franchise

to the blacks, and also sought to enforce the African Land and Husbandry Act in all black areas. His predecessor, Huggins had applied the Act to selected areas only in an effort to convince the blacks of the

advantages of sound animal- and field-husbandry practices. Todd's efforts led to widespread discontent in black areas. Todd also turned his attention to miscegnation, and while of minor importance

only, this proved to be a highly contentious and emotional issue. A rift developed between Todd and the UFP, matters coming to a head when Todd was accused of abrogating the principles of collective cabinet

responsibility, and his entire cabinet resigned, thereby forcing him from office. Todd was succeeded by Sir Edgar Whitehead, who remained Prime Minister until the upset election in 1962 when the

Rhodesian Front came to power. Whitehead's tenure of office was characterised by escalating violence not only in Southern Rhodesia, but also in other Federal territories. Whitehead's first task in Southern

Rhodesia was to revise the 1923 Constitution, which still contained clauses empowering the British Government to withold assent to Bills of the Legislative Assembly of Southern Rhodesia. (This right had never been

exercised.) His aim was in fact independence. Talks between the two governments led to a series of constitutional conferences starting in 1960. Joshua Nkomo, leader of the National Democratic Party at that time,

agreed to co-operate with Whitehead on a new constitution, and denounced violence. The new constitution was finally accepted after a referendum by some 42 000 votes to 22 000. When the constitution

was presented to the House of Commons in London certain changes had however been made to the original proposals which had been accepted during the referendum. These changes in fact increased the British

Government's power to interfere in the process of government in Southern Rhodesia. The constitution did have certain merits on the other hand, as provisions had been made for black advancement. It

contained a Bill of Rights aimed at preventing discriminatory legislation, and providing a safeguard against laws infringing on civil liberties. Provision had been made for a Constitutional Council that would act

as a watch- dog as regards legislation, ensuring that this was not inconsistent with the Bill of Rights. The bill also opened up the franchise to a greater extent than ever before, and for the first

time permitted blacks to sit in the Legislative Assembly. They would have become the majority in due course. The Constitution required the support of the blacks however, and this was not forthcoming. While Nkomo

and Ndabaningi Sithole had agreed to the provisions of the constitution, they subsequently changed their minds and their more extremist followers started a campaign of intimidation to prevent blacks from

registering as voters. Their actions amounted to a boycott of the constitution. |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

BLACK LEADERSHIP IN FEDERATION YEARS Whitehead's inability to cope

effectively with the black extremists is reflected by the cat-and-mouse game they played with him. The African National Congress (ANC) was banned in 1959, and the extremists promptly formed the National Democratic

Party which Whitehead banned in December 1960. The leaders were undeterred, and started yet another organisation, the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), and acts of terror continued. ZAPU was banned in

September 1962, but by then lawlessness was rife and it remained so until the Rhodesian Front Party restored order. Nkomo set up the People's Caretaker Council (PCC) in 1963, insisting that this was

not a political organisation. Sithole broke with Nkomo at this stage, and formed the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). Robert Mugabe, leader of the Zimbabwe Independence People's Army (ZIPA), was one of the

members of ZAPU who broke with Nkomo in 1963 to help Sithole with the formation of ZANU. Nkomo and Mugabe are today again united in the Patriotic Front, a development which took place during the Geneva Conference

in 1976. The power of the black extremists was broken for the time being and peace restored when Ian Smith succeeded to the premiership in 1964. He banned ZANU and the PCC-ZAPU, and imprisoned Nkomo

and Sithole along with other leaders. They were released from detention in 1974, at the insistence of international pressure which held that there could not be meaningful talks on resolving the Rhodesian

settlement issue while the black leaders were imprisoned.

FEDERATION LIMPS ALONG By the late 1950s it was becoming increasingly clear that the Federation's days were numbered. The black leaders in Nyasaland, Banda and Chipembere, were willing to use force and

violence to get their way, and were interested in independence, not Federation. The same applied in Northern Rhodesia where Kaunda led the black nationalists. Banda and other black leaders were in

fact jailed in 1958 for plotting against the Governor of Nyasaland. The British Government accepted in 1962 Nyasaland's right to secede, and in 1963 the Northern Rhodesia Legislature passed a motion demanding

secession from the Federation. Federal Prime Minister Welensky argued vehemently that no provision had been made for secession from the Federation without the consent of all five parties (the Federal

Government, the three partner countries and Britain) but it was increasingly clear that the Federation could not work if one or more of the states involved wanted out. The 1959 Devlin Commission Report on

the state of emergency in Nyasaland, and the Monckton Commission charged with preparing material for the 1960 Federal Review Conference ultimately sounded the death knell of the Federation. Devlin's

report was severely critical of British policy in Nyasaland, and by implication in the Federation, while the Monckton Commission concluded that the Federation could not survive except by force, or the introduction

of massive changes in racial legislation. Before dissolving the Federation, the British Government promised both Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia independence, but refused to give Southern Rhodesia a

similar commitment.

IAN SMITH AND THE RHODESIAN FRONT However, before dealing finally with the final dissolution of the Federation and the events that culminated in UDI on 11 November 1955, it is as well to briefly trace the rise of the

Rhodesian Front and Ian Smith, who has played so dramatic and dominant a role in the Rhodesian political scene over the past 13 years. Winston Field became leader of the newly formed right-wing

Dominion Party (DP) in 1957, and won a major by-election when he defeated Evan Campbell, prominent member of the United Federal Party (UFP), for a federal seat. The DP came close to ousting the UFP in the Southern

Rhodesia in the 1958 elections when it won 13 seats to the UFP's 17. Continuing unrest, Whitehead's failure to cope with it, public dismay at the 1961 Constitution, and the drift to the left in

Rhodesian politics had all led to increasing disenchantment with the UFP. The Rhodesian Front, formed by the Dominion Party and dissenters from the UFP in March 1962, (these included Smith, who had resigned from

the UFP over the 1961 Constitution) caused an upset during the December elections, coming to power with a majority of five seats in the 50-member Legislature. Winston Field became Prime Minister,

with Ian Smith as his deputy. During the whole of 1963, until Smith succeeded him as Prime Minister in April 1964, Field was engrossed in dismantling the Federation following a vain bid to secure Rhodesian

independence.

THE FEDERATION DISINTEGRATES Acting

on the advice of Welensky, Field at first refused to attend the Victoria Falls Conference where the Federation was to be finally dismantled, arid demanded that he be given a prior commitment on independence. The

British Government was not prepared to give this undertaking, and R.A. Butler, MacMillan's First Secretary of State in charge of Central African Affairs, managed to wriggle out of a tight spot by convincing Field

that Southern Rhodesia 'like the other territories will proveed through the normal proceed to independence.' He further persuaded Field that Southern Rhodesia could not achieve independence while still a member of

the non-independent Federation, and that a number of financial, defence, constitutional, and similar matters had to be ironed out before self-governing dependencies could become independent. Field

was won over, albeit reluctantly, and he attended the Victoria Falls Conference in June 1963. The rest is history. The Federation was dissolved, Southern Rhodesia inherited massive Federal debts, and Field came

away without his independence. Field later claimed that Butler had given him a categorical assurance that Rhodesia's demand for independence would be dealt with immediately, and would present no problems, provided

he attended the conference. This assurance was allegedly repeated in the presence of Smith. Butler however, flatly denied that he had ever made such a commitment.

ROAD TO UDI Field's failure to resolve the independence issue led to his resignation in April 1964, and he was

succeeded by Ian Smith, then little known beyond the ranks of the RF. He was considered to be a raw colonial and a hard right-winger particularly by British politicians and civil servants. Within 20 months of

taking office, Smith had a larger following than any of his predecessors, and was known throughout the world, having defied Britian, the Commonwealth, the UN, in fact the world, by his Unilateral Declaration of

Independence (UDI) on 11 November 1965. When Smith came to office the general expectation was that he would immediately assume independence, but he first turned his attention to gaining support in

Rhodesia, and toured the country, addressing scores of gatherings. His theme was independence, and the need to explore peaceful avenues open to Rhodesia. Negotiations between Rhodesia and the British

Government were resumed. Smith visited London in September 1964 for talks with Home and Sandys, but the matter of testing African opinion proved to be the stumbling block to a concensus between the two

governments. Smith returned to Rhodesia, optimistic that agreement could be reached with Britain. History however intervened in October 1964 when the Labour Government narrowly defeated the Conservative Party, and

Harold Wilson came to power. Smith and Wilson were totally incompatible - not only politically, but also personally, and the dislike and mistrust between them did nothing to ease the situation

between Britain and Rhodesia. Exchanges between the two men were marked by increasing acrimony. When Smith called an election in May 1965, and the RF won 50 of 65 seats in Parliament, the stage was set for

UDI, and the Salisbury Government put in train plans to implement it. These included the identification and isolation of senior civil servants who were opposed to UDI, the development of an effective propaganda

arm in the Department of Information, and political control of the Rhodesian Broadcasting Corporation.

SMITH'S UNILATERAL DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE Wilson was fully aware of the direction of events in Rhodesia, and did make attempts to

forestall UDI. He dispatched two of his ministers to Rhodesia, and invited Smith to visit London in October. When this failed, he visited Rhodesia personally towards the end of October 1965, making an eleventh

hour bid to avert UDI. His efforts failed, and Ian Smith announced his country's Unilateral Declaration of Independence on 11 November 1965. The British Government retaliated swiftly. Rhodesia was

removed from the sterling area, British exports of capital goods to Rhodesia were banned, the purchase of Rhodesian tobacco was discontinued, Rhodesia was denied access to the London capital market, the

Commonwealth Sugar Agreement was terminated (insofar it affected Rhodesia), and Rhodesian passports were declared illegal documents. The Southern Rhodesia Act outlawed most trade with Rhodesia on 16 November, and

on 5 December the British Government seized Rhodesian assets worth £9 million in the British Reserve Bank. In spite of these measures, Wilson's predictions that the Rhodesian government would

collapse "within a matter of weeks" did not prove true. Britain took the Rhodesian matter to the UN Security Council on 9 April 1966 and obtained the world body's consent to impose the "Beira

blockade" to prevent oil destined for Rhodesia from reaching the Mocambique port. The British government expected the oil embargo to bring the Rhodesian government to its knees. At the January 1967

Commonwealth Conference. Wilson again emphasized that the "rebel government" could not survive an oil embargo for long, and that the rebellion would end in weeks rather than months. British warships prevented

several tankers from reaching Beira during April 1966 but most of Rhodesia's oil requirements had by then been rerouted through other Southern African ports.

LONG ROAD OF FUTILE NEGOTIATIONS The British Government announced at the end of April that "informal

exploratory talks" with Rhodesia would take place to determine whether a basis for negotiated settlement still existed. These talks continued until August, with Britain demanding Rhodesian surrender as a

prerequisite to official negotiation. Although Rhodesia did accept certain British proposals, no major progress was made. Smith was again invited on 19 September for further talks with the British Prime Minister

on board the cruiser HMS Tiger. These discussions took place on 2 December 1966'. Britain now made an additional demand, that Rhodesia return to "legality" by renouncing UDI and accepting a British

governor for Rhodesia. Rhodesia's rejection of these preconditions led to Britain's formally withdrawing all offers of an independent constitution, and adopting the standpoint that there could be no

independence before majority rule (NIBMAR). Britain then went to the UN and appealed for selected mandatory sanctions to include oil. The world body readily agreed to this, thereby violating its own charter.

British imports from Rhodesia dropped to 15 percent, and those to West Germany by 87 percent of their original level, while German exports to Rhodesia soon rose to 103 percent of the 1965 figures. After UN

selective mandatory sanctions had been invoked in 1967, 65 percent of Rhodesia's foreign trade went through South Africa (as compared to 35 percent in the past), and this percentage soon increased. Sanctions have

therefore remained a poorly enforced policy. Despite several attempts to restart talks during 1967 and 1968, relations between London and Salisbury deteriorated considerably after appeals by three

convicted terrorists against their death sentences by the Rhodesian Court of Appeal. The right of appeal to the Privy Council no longer existed under the 1965 constitution. Despite a last-minute reprieve granted

by the Queen, and a subsequent application to the Appelate Division of the High Court, the application was dismissed, and the three terrorists were executed on 6 March. Rhodesia had again demonstrated the

country's sovereignty. The Appelate Division of the High Court of Rhodesia ruled on 18 September 1968 that the government was also the de jure government of Rhodesia. Despite the fact that Rhodesia

had increasingly and convincingly demonstrated her independence, attempts to find a political settlement continued. Talks between Smith and his British colleague Wilson were held aboard HMS Fearless on 10-13

October 1968. The Tiger proposals remained basically unaltered, except to omit the interim government Wilson had earlier regarded as a prerequisite for any just test of black opinion. The proposals were again rejected,

despite the fact that Britain was now prepared to grant independence on a basis which would leave political power in the hands of the whites. The Salisbury government stated that it was unwilling to accept the

proposed "mechanisations" for constitutional amendment. |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Premiers Smith and Wilson during the “Tiger talks” onboard HMS Tiger |

|||

|

|

CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGES Further talks took place between

Thompson and the Rhodesian government before the end of 1968, but nothing came of these. Rhodesia raised her new flag on 11 November, and officially rejected the Fearless proposals a week later. The country turned

her attention inwards during 1969, and determined to bring her own house in order. In May Prime Minister Smith made it clear that Britain's "intractable attitude" had ended all hope of a negotiated

settlement. He went on to announce a new constitution, to be published in a White Paper on 20 May. The referendum held exactly one month later, resulted in an 81 percent poll in favour of a republic, indicating

that 72,5 percent of the voters had accepted the new constitution proposed by the Rhodesian Front Government. The constitutional proposals were published on 11 September 1969, and passed by Parliament on 17

November. Clifford Dupont, the officer administering the government, signed the Bill on 29 November. Constitutional and administrative ties were not the only links to be severed. In December 1969 for

instance, the University of Rhodesia decided not to confer University of London degrees in future, but to award its own. Rhodesia became a republic in March 1970, whereupon the US immediately closed her consulate

in Salisbury. In spite of this, the United States and Britain jointly vetoed a United Nations proposal for total mandatory sanctions against Rhodesia. Rhodesia's first president, Mr Clifford Dupont, was sworn in

on 16 April 1970.

PEARCE COMMISSION The next major attempt at a solution came more than a year later when Lord Goodman, close confidant of Wilson, arrived in Salisbury on 30 June 1971. Various new proposals were discussed, but the

initiative came to an abrupt end when the Socialists were ousted by a Conservative Government in Britain. The new Prime Minister, Edward Heath, sent Home, his Foreign Secretary, to Rhodesia, and this round of

talks in November 1971 led to London and Salisbury agreeing on a formula for independence. The Rhodesian Prime Minister and the British Foreign Secretary agreed on the following five principles:

1) Unimpeded progress towards majority rule; Despite Rhodesia's misgivings on the last point - the

acceptability of the settlement to the people of Rhodesia as a whole - both parties signed the agreement setting out the proposals in Salisbury on 24 November, 1971. The commission assigned to test Rhodesian

opinion was led by Lord Pearce, and arrived in Rhodesia on 11 January 1972. Within the week, violence erupted in such centres as Salisbury, Gwelo, and Umtali. The African National Council (ANC), led by Bishop Abel

Muzorewa, came out against the settlement propo- sals, thereby driving many followers of Joshua Nkomo (ZAPU), and Ndabaninge Sithole (ZANU) into the ranks of the ANC as these detained black leaders also continued

to oppose any settlement that did not promote a rapid transition to black majority rule. When the Pearce Commission left Rhodesia on 11 March 1971, it had recorded a massive "no" from the black

population, whereas 98 percent of the 100 000 whites had said "yes", and 97 percent of the coloureds, and 96 percent of the Asians had expressed themselves in favour of the new Anglo-Rhodesian settlement

proposals. Home later told the House of Commons: "I would ask the Africans to look again very carefully at what they have rejected ... the proposals are still available because Mr Smith has not withdrawn or

modified them". As it happened, black rejection of the proposals failed to generate any new plans, but resulted in a stalemate that was to last until the Kissinger initiative in 1976.

EMERGING TERRORIST CAMPAIGN Terrorists attacked

a white farm in the Centenary area on 21 December 1972. This incident marked the beginning of a guerrilla war that continues with varying intensity until the present. As tension mounted throughout the northern

areas of the country, the government in Salisbury decid- ed to close the country's border with Zambia until such time as the Zambian authorities gave the assurance that no anti-Rhodesian terrorists would be

harboured in their country. Zambia closed her border with Rhodesia on 1 February, 1973 and has kept it closed, despite Rhodesia's decision, three days later, to reopen her side of the border. The border area

remained tense as more and more landmine and shooting incidents were reported. The most significant of these encounters occurred in the vicinity of the Victoria Falls on 15 May 1973, when two Canadian tourists

were killed by rifle fire from Zambian side of the Zambezi River. On 5 July, a large gang of armed terrorists abducted 295 African pupils and teachers from St Alberts mission in the north-east region

of the country. Rhodesian security forces succeeded in rescuing all but eight of those abducted. In August serious unrest erupted on the campus of the University of Rhodesia following initial student protest about

low wages paid to African workers at the university. The increased guerrilla activity had also forced the Rhodesian government to extent national service from nine months to one year. In June, while the Victoria

Falls incident was still clear in every mind, several officials from the British Foreign Office arrived in Rhodesia for talks with the Rhodesian government, and leaders of the ANC. During the last months of 1973,

further terrorist incursions finally became such a menace that the Rhodesian government started offering cash rewards for information leading to the capture or death of terrorists.

SOUTHERN AFRICA CALLS THE TUNE The Portuguese coup on 25 April

1974 had an immediate and wide-ranging effect on the political landscape of Southern Africa. By the middle of the year, a Frelimo-led caretaker government had been installed in Lourengo Marques, which meant that

the port of Beira, hitherto one of Rhodesia's main trade outlets, was no longer available. The same applied to Lourengo Marques. A new railway link from Rutenga to Beit Bridge was completed in September. This has

provided an additional railway line between Rhodesia and South Africa that has now become Rhodesia's lifeline to the outside world. In the general election, held on 31 July, the Rhodesia Front Party again won all

50 white constituencies. South African Prime Minister John Vorster launched his famous detente-with-Africa policy during a speech to the Senate in Cape Town on 23 October 1974. Pres Kenneth Kaunda of

Zambia reacted a few days later, welcoming the speech as "the voice of reason for which Africa and the world have been waiting". Realising that the Portuguese coup had drastically changed the situation

for white Southern Africa, and for Rhodesia in particular, Kaunda now encouraged black Rhodesian nationalists to unite with a view to negotiating with the Rhodesian government, a course both he and Vorster openly

favoured. Several leaders, including Sithole and Nkomo, were released as result of Vorster's detente efforts. Black leaders met in Lusaka, and on 9 December 1974 they signed an agreement uniting ZAPU, ZANU and

FROLIZI (Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe), under the banner of the African National Council of Bishop Muzorewa. Two days after the meeting, Smith informed the country that the government was to hold a

constitutional conference with the nationalists, and that nationalist leaders still in detention would be released. The Prime Minister indicated that he expected terrorist incursions in Rhodesia to cease in

reciprocation. South Africa also expected acts of terrorism to cease, and Vorster confirmed that South African police units originally sent to Rhodesia in 1967/68, would be withdrawn if terrorists were to

discontinue their own activities. Despite a definite lull in terrorist incursions, these soon increased again, and on 10 January 1975 the Rhodesian government stopped the release of political detainees. Security

measures were again tightened, and military officials later admitted that their relaxed vigilance during the initial stages of detente had enabled terrorists to step-up activities in certain areas of Eastern and

North-Eastern Rhodesia. Sithole was again arrested in March 1975 on charges of plotting the assassination of certain of his political opponents. This caused an immediate outcry in African circles, and pressure was

brought to bear on South Africa to effect his release. Smith led a high-ranking Rhodesian government delegation to a conference with the South African Prime Minister on 15 March. Herbert Chitepo,

leader of the ZANU movement, was assassinated by political rivals in Lusaka four days later, revealing the serious rift within the nationalist movement. The Rhodesian Special Court renewed the detention order on

Sithole at the beginning of April, but he was released on 6 April following an appeal by Muzorewa, supported by the South African government. Efforts to bring the Rhodesian government and the various nationalists

together, were intensified during the next two months, the South African government playing a prominent role in attempts to bring the interested parties to the conference table. Tension again mounted among

supporters of the various black movements. Thirteen people were killed and 28 injured when the police opened fire on a crowd of several thousand blacks on 2 June. The initial talks held between Smith

and the ANC leaders on 15 June 1975 ended in a deadlock as the parties were unable to agree on the venue for a constitutional conference. The Rhodesian Minister of Information and several MP's flew to Lusaka ten

days later for talks with Kaunda, and reached agreement for a conference to be held on neutral ground soon after their arrival. The conference was held on the bridge near the Victoria Falls in railway carriages

provided by the South African Railways on 25 August. Kaunda and Vorster attended the meeting which may be regarded as the climax of the detente exercise, despite the fact, that Smith and the black nationalists

failed to reach agreement. The ANC disintegrated after the Victoria Falls meeting with Joshua Nkomo forming his own internal wing, and Muzorewa and Sithole leading the external faction. The front-line presidents,

notably Nyerere of Tanzania and Machel of Mozambique believed that political settlement was impossible, and this led directly to the establishment of the Zimbabwe People's Army (ZIPA), a military group consisting of

former ZANU and ZAPU cadres. ZIPA forces, led by a Moscow-orientated, 18-man High Command under former ZANU Field Commander Rex Nhongo, launched a new offensive against Rhodesia on 18 January 1976. This onslaught

was perhaps the single most significant element in the political struggle for Rhodesia, and quickly led to an escalation of the conflict, especially along the Mogambique border where incidents have become

increasingly common. South African and Cuban involvement in the Angolan civil war, and the threat of Cuban involvement in Rhodesia, once more fixed the international spotlight on Southern Africa and the Rhodesian

issue, and led to the Kissinger initiative and the abortive Geneva Conference. Smith met Kissinger, America's Secretary of State, for talks in Pretoria, and returned to Rhodesia to announce that he

had accepted the Kissinger proposals calling for establishment of an interim government and a handover to black majority rule within two years. The proposals included American-British assurances, and guarantees

for the white minority. The agreement called for a halt to sanctions and the terrorist war. The black nationalists, notably Robert Mugabe of ZIPA, who claims to have assumed command of ZANU's external wing from

Sithole, and a number of front-line presidents, all rejected the Kissinger proposals, and intimated that they had never been party to them - the impression Kissinger had given according to Smith and Vorster. The Salisbury Government and the black leaders assembled at Geneva under the chairmanship of Mr Ivor Richard, a British UN representative in October 1976 to try and see how the proposals could best be

implemented. However, the conference was marked by dissent among the black delegates from the beginning and when it broke up for Christmas no headway had been made. In fact the assembly of the conference

originally scheduled for mid-January 1977 has been indefinitely postponed because of the deadlock. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||